Competency

Working with a buddy, we discovered you need three things to cross the competency gap.

What’s the competency gap?

That’s the soul-crushing gap between working on a tutorial and building a system. It’s the difference between finding a StackOverflow answer and knowing whether to use it. It’s knowing enough about what’s going on and where things are that you can build and test systems that do what you want them to do.

Well that sounds useful, what are these three magical tokens?

Glad you asked. The first one is you need to have an idea.

Wait, what?

Right, you need to have an idea of what you’re doing.

Isn’t this obvious?

No, actually. This is a big deal. (It’s HUUUGE!). This is where almost everybody breaking into coding gets lost. You’ve got to have a basic idea that guides you through the next step.

What does that look like?

I think visually, so I draw a picture. I use arrows, circles, boxes, cloud shapes to get some idea of what’s going on.

This not only helps me get to work, it really helps me when I’m working with other senior devs. Senior devs like to just do things their way, but when working with another senior dev, forcing them so see a picture, we can make collaborative improvements in our thinking without losing too much time.

OK, so I have an idea of what I’m doing, now what?

Now you’ve got to start doing things while the frustration levels are manageable.

How is this good advice?

Every programming session on the planet ends in frustration or interruption. Well, not every one, there are the one in a thousand sessions when we actually run out of things to do. In my experience though, we never really run out of things to do, we just run out of time. So, the expectation is that we’ll work until we get tired, worn out, or confused. A lot of people get that way and think they’re just too dumb, not as smart as anyone else, unable to do the job. I don’t care who you are, you hit your limits.

What does it look like before the frustration settles in?

What I’m looking for is a willingness to engage. This looks like not knowing the answer but trying things anway, chasing down possibilities, refactoring anything that looks awkward as I go, reviewing how things fit together often, thinking about how things plug together. The enemy to this kind of productivity is, “there’s got to be a better way.” There always is, but until we know it, we go forward anyway. Think about the smart people breaking into the software business that are stymied by really arrogant destructive people that want to be the boss. Don’t be a boss. Be a leader by getting things moving in the same direction.

All of this boils down to taking steps and refusing anything or anyone to get in your way. Writing systems isn’t like folllowing a tutorial. You’re unsure but that’s not slowing you down. Some people think they have a better idea, but that’s either collaborative or not allowed near you. You’re going to wear down, but you’re going to get used to working with things that are broken and leave it alone without beating yourself up.

What’s the third trick?

Refine with confidence. In other words, it’s not ever done, it’s working, and that’s OK. My abilities and insights grow over time. I’ll use more of this when I have it.

Some types of books and tutorials belie this reality. We want to get a technology under our belt, but we never quite come up with solutions like the ones we’re reading and using. We obviously aren’t as good as them, right? Wrong. They’ve just refined their ideas until there was some identifiable value they could demonstrate. Thinking there are right answers this business slows down the delivery of working systems. Use your tests, your users, your reviews, and your good sense to do a good job, but don’t let that keep you from pushing solutions.

So, this is interesting, do you have a real use case? Prove to me these few minutes were well spent.

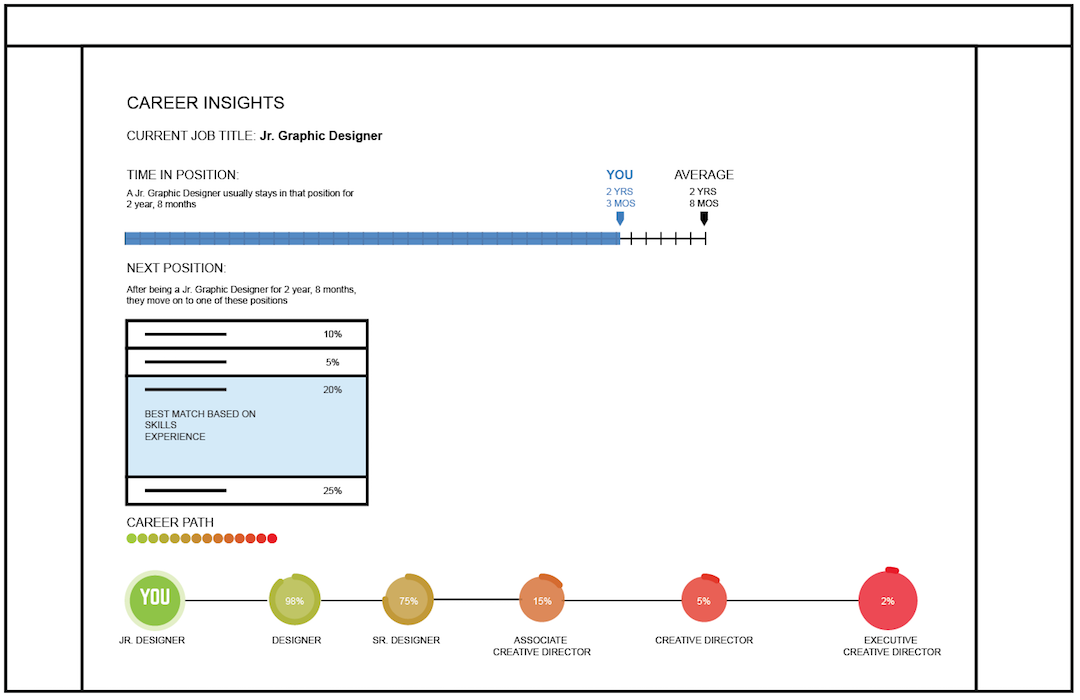

Sure. This week I wanted to build an API for a page that will look something like this:

I knew I had some of this data available, but not all of it. I knew what job, skills, and education someone has, and I knew what skills and education was expected for a new job, but I didn’t have an obvious way to compare these things. I didn’t have time to work on things immediately, so I was able to I wake up a few mornings with new ideas about how this all could come together. When it was time to actually do the work, I did a little bit of doodling while I started to get an idea.

This won’t mean much to anyone, not even me today. That’s OK, I could see that there were gaps in how I wanted to do things. So, I made a mental list, “I’m going to review what I have, figure out how to get the data, do something mathy, and return something that can be used downstream.”

Wait, stop, that list looks about as non-tutorial-like as I’ve ever seen.

EXACTLY. Now you’re getting it. I had an idea, I was able to do work. I was able to be wrong and OK with that. The actual code writing looked like this:

I re-read the file I was working on, fixing a poorly-named variable and a poorly-named method in my code. Things seemed to make sense as I explained to myself what I had so far. I then looked at getting data. I ended up writing a database view to make things really easy and pretty soon I had the data I needed so I could do something mathy. I ended up calculating a z-score and converting it into a percentile to normalize skill values. I could then use this value to weight a skills match. It made sense for what I was doing, but I didn’t know how I’d approach it until I started Googling around for broad terms while I was being creative. Meaning, if I told you that the z-score approach was what was needed, that this was the best answer, it would have taken you out of the process of coming up with something. There are at least 10 possibilities for how that could have been done, and this one works about right. I didn’t let perfectionism steal my productivity.

After I got this done, I went to bed tired. The next morning I woke up with a new idea. I took 10 minutes and refined my work. A few hours later, I made the interface to the class a little easier to use. The next night I built a couple of tools that used this job matching functionality as I needed it. I added a note about caching and optimizing this code in a future version of this code.

For this whole experience, I didn’t know what I was building for 95% of the time. But I built the system. People breaking into the software business don’t know these things. Knowing how to get an idea, work with frustrations, and improve at a human pace can be all you need to get out of the “I’m just learning about this stuff” mentality and into the “I’ve got this” mentality.